|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In 5G NR, Polar coding is the “small-packet specialist” that protects the control plane and the always-critical broadcast information. That choice makes sense because control messages are short but decisive. A single missed DCI on PDCCH or an unreliable UCI on PUCCH can break scheduling, HARQ timing, and link adaptation even when the data channel is fine. Polar coding starts from an interesting idea called channel polarization. Instead of treating all coded bit positions as equally fragile, it intentionally reshapes them into a set of “good” positions and “bad” positions. The good positions carry the real information bits. The bad positions are filled with frozen values that the receiver already knows, so they act like built-in anchors during decoding. In real NR, this is not used in its pure textbook form. The information bits are usually protected by CRC (and sometimes extra parity-check structure), not because CRC is a generic checksum, but because it becomes an active part of the decoder’s decision logic. The decoder explores multiple candidate paths and then uses CRC to pick the one that is self-consistent. Finally, rate matching makes the code fit the actual number of physical resources by puncturing, shortening, or repeating bits, so the same Polar coding framework can adapt to many different control payload sizes and slot allocations. The overall intuition is simple. NR uses LDPC where throughput and parallel decoding dominate, but it uses Polar where “short, reliable, and predictable” matters most, because the control plane needs robustness without relying on long blocks to average out the noise. Key Idea of Polar CodingPolar coding key points become clearer when you view it as a very structured “FFT-like” linear transform plus a decoding logic that turns reliability into an explicit design knob. The encoder is not just adding redundancy in a generic way. It applies a generator matrix built from repeated Kronecker products of a small kernel, so each stage mixes bits in a recursive pattern and creates the polarization effect as a mathematical consequence of that structure. This is also why the implementation cost is manageable, because the lower-triangular, recursive form leads to an O(N logN ) style flow rather than a dense-matrix multiply. On the receiver side, NR does not rely on plain successive cancellation because one early wrong decision can contaminate the rest of the tree. Instead it uses list decoding, where the decoder keeps multiple candidate paths and continuously ranks them with a path metric, then uses CRC as an active selector to collapse the list to the one path that is globally consistent. The “which bit positions carry information” question is also not left to runtime computation. NR uses a pre-defined reliability sequence, so the transmitter simply picks the most reliable sub-channels for a given payload and freezes the rest, which makes the behavior predictable and standardizable. Finally, practical resource allocation forces rate matching, so the coded stream is pushed through interleaving and a circular-buffer style selection to realize puncturing, shortening, or repetition while trying to preserve the polarization gain. Systematic vs non-systematic is then a packaging choice around the same core engine, where systematic mapping can make the information bits visible in the codeword without changing the fundamental block-level robustness. Polar coding in NR is built around a very specific linear transform, not an arbitrary parity construction. The key points become clearer when you connect three things together. These are the generator matrix that creates polarization, the reliability-based selection of bit positions, and the CA-SCL decoding logic that makes short blocks work well in practice. Generator matrix and encoder structureThe heart of Polar coding is the generator matrix GN. It is constructed from repeated Kronecker products of a small kernel matrix, so the encoder becomes a staged transform where each stage mixes bits in a predictable way. This staged structure is what produces channel polarization and it also makes the encoder efficient to implement.

Frozen bits and information-bit placementOnce the transform defines polarized sub-channels, the transmitter must decide where to place the real payload. Frozen bits are the practical rule that turns sub-channel reliability into a deterministic mapping. In NR, this mapping is designed to be predictable and standardized rather than computed on the fly.

Decoding engine: SCL + CRC (CA-SCL)Polar decoding is naturally sequential because it follows the decoding tree implied by the transform. The weakness of plain SC is that one wrong decision early can contaminate everything after it. NR uses list decoding to keep multiple hypotheses alive, and then uses CRC as an active winner selector, which is why Polar performs strongly for short control payloads.

Rate matching to fit physical resourcesReal NR allocations rarely provide a neat power-of-two number of coded bits. Rate matching is therefore not a minor detail. It reshapes the Polar output stream to the exact bit count E required by the physical mapping, while trying to keep the effective polarization gain after interleaving and selection.

Systematic vs non-systematic mappingSystematic Polar is mainly an output-format choice around the same core transform and decoding logic. It can make the codeword “look friendlier” to downstream processing and may slightly improve BER, while the block-level robustness remains dominated by CA-SCL behavior.

Deep Dive into Specification

5.3.1 Polar codingThe bit sequence input for a given code block to channel coding is denoted by c0, c1, c2, c3, ..., cK−1, where K is the number of bits to encode. After encoding the bits are denoted by d0, d1, d2, ..., dN−1, where N = 2n and the value of n is determined by the following: Denote by E the rate matching output sequence length as given in Clause 5.4.1; If E ≤ (9/8)·2(⌈log2E⌉ − 1) and K/E < 9/16 n1 = ⌈log2E⌉ − 1; else n1 = ⌈log2E⌉; end if Rmin = 1/8; n2 = ⌈log2(K/Rmin)⌉; n = max{ min{ n1, n2, nmax }, nmin } where nmin = 5. UE is not expected to be configured with K + npc > E, where npc is the number of parity check bits defined in Clause 5.3.1.2. This section of the 3GPP specification describes the logic for determining the mother code block size (N) for 5G NR Polar coding. In Polar coding, the mother code size must always be a power of 2 (N = 2n). However, the actual number of bits requested by the physical layer (E) is often not a power of 2. This procedure defines the mathematical rules to select the best value of n (and therefore N) to balance performance and resource efficiency. Key Variables

Step-by-Step Logic Breakdown1. Calculating n1 (The rate-matching-driven size) The first part decides whether to use a larger or smaller power of 2 based on how “tight” the rate matching is. If the target length E is only slightly larger than a power of 2 (within a defined threshold) and the code rate K/E is very low, the procedure may choose a smaller n1 to reduce complexity and avoid oversizing the mother code. Otherwise it uses the natural choice based on ceil(log2(E)), meaning it selects a power of 2 that can accommodate the required output length. 2. Calculating n2 (The minimum code-rate constraint) This step enforces a minimum effective code rate through Rmin. It computes the smallest power-of-2 exponent that keeps the information payload from being overly “diluted” by a too-large mother code size. In practice it means choosing n2 = ceil(log2(K / Rmin)). 3. Final selection of n The final value of n is chosen by balancing multiple constraints. It is bounded above by a maximum supported size (nmax) and bounded below by nmin, so the result is never smaller than the minimum supported block length. Conceptually, the logic takes the smallest feasible exponent that satisfies both the rate-matching condition (n1) and the minimum-rate condition (n2), then clamps it within the allowed range. The “Golden Rule” Constraint The final sentence adds an important configuration rule. A UE should never be configured such that the information bits plus parity check bits (K + npc) exceed the available physical resources (E). If that happened, the implied code rate would exceed 1, which is not meaningful for channel coding and would make successful transmission impossible. Example >Suppose we have the following scenario for a PDCCH transmission:

1. Find n1 (Rate Matching Factor) First, we look at the conditional block:

Because the combined condition is False, we follow the

2. Find n2 (Code Rate Factor) Next, we ensure we don't violate the minimum code rate Rmin:

3. Final Calculation of n Now we apply the final formula:

Result: The exponent n is 7, so the Mother Code Block size is N = 128. Summary of what this achieves In this example, the system chose a mother code of 128 bits to carry your 40 information bits, eventually fitting them into the 100 bits of physical space. Since E < N, the rate matching engine will perform puncturing or shortening to remove 28 bits from the mother code before transmission. 5.3.1.1 InterleavingThe bit sequence c0, c1, c2, c3, ..., cK-1 is interleaved into bit sequence c′0, c′1, c′2, c′3, ..., c′K-1 as follows: c′k = cΠ(k), k = 0, 1, ..., K - 1 where the interleaving pattern Π(k) is given by the following: if IIL = 0 Π(k) = k, k = 0, 1, ..., K - 1 else

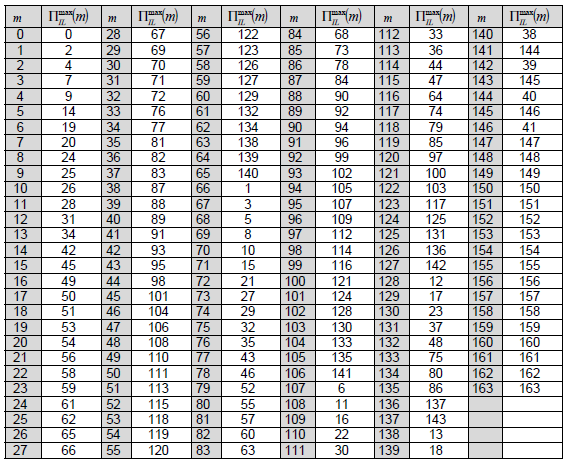

end if where ΠILmax(m) is given by Table 5.3.1.1-1 and KILmax = 164. < 38.212-Table 5.3.1.1-1: Interleaving pattern ΠILmax(m) >

In Polar coding, some bit positions are more reliable than others. Interleaving ensures that the information bits are distributed in a way that maximizes the performance of the Successive Cancellation decoder. How it Works:

Interpretation of the codeFollowing is the interpretation of the codeblock

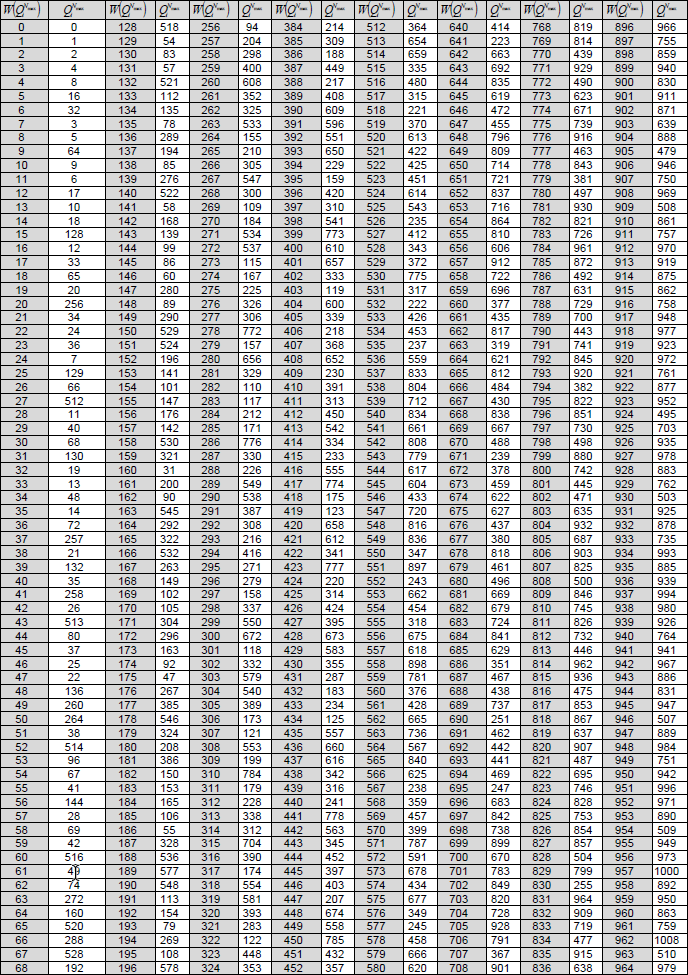

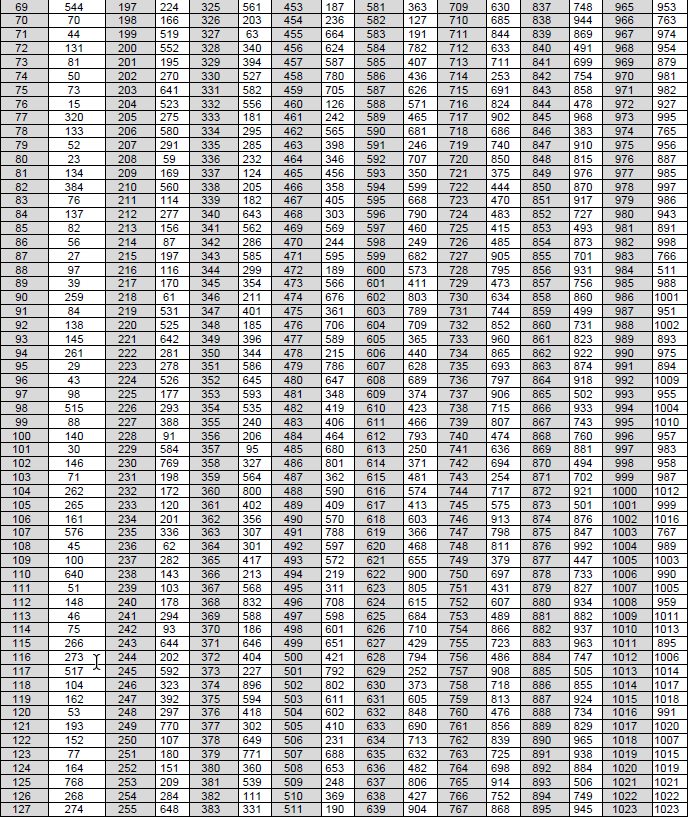

5.3.1.2 Polar encodingThe Polar sequence Q0Nmax−1 = {Q0Nmax, Q1Nmax, ..., QNmax−1Nmax} is given by Table 5.3.1.2-1, where 0 ≤ QiNmax ≤ Nmax − 1 denotes a bit index before Polar encoding for i = 0, 1, ..., Nmax − 1 and Nmax = 1024. The Polar sequence Q0Nmax−1 is in ascending order of reliability W(Q0Nmax) < W(Q1Nmax) < ... < W(QNmax−1Nmax), where W(QiNmax) denotes the reliability of bit index QiNmax. For any code block encoded to N bits, a same Polar sequence Q0N−1 = {Q0N, Q1N, Q2N, ..., QN−1N} is used. The Polar sequence Q0N−1 is a subset of Polar sequence Q0Nmax−1 with all elements QiNmax of values less than N, ordered in ascending order of reliability W(Q0N) < W(Q1N) < W(Q2N) < ... < W(QN−1N). Denote Q̄IN as a set of bit indices in Polar sequence Q0N−1, and Q̄FN as the set of other bit indices in Polar sequence Q0N−1, where Q̄IN and Q̄FN are given in Clause 5.4.1.1, |Q̄IN| = K + nPC, |Q̄FN| = N − |Q̄IN|, and nPC is the number of parity check bits. Denote GN = (G2)⊗n as the n-th Kronecker power of matrix G2, where G2 = [ 1 0 1 1 ]. For a bit index j with j = 0, 1, ..., N − 1, denote gj as the j-th row of GN and w(gj) as the row weight of gj, where w(gj) is the number of ones in gj. Denote the set of bit indices for parity check bits as Q̄PCN, where |Q̄PCN| = nPC. A number of (nPC − nPCwm) parity check bits are placed in the (nPC − nPCwm) least reliable bit indices in Q̄IN. A number of nPCwm other parity check bits are placed in the bit indices of minimum row weight in Q̄IN, where Q̄IN denotes the (|Q̄IN| − nPC) most reliable bit indices in Q̄IN. If there are more than nPCwm bit indices of the same minimum row weight in Q̄IN, the nPCwm other parity check bits are placed in the nPCwm bit indices of the highest reliability and the minimum row weight in Q̄IN. Generate u = [u0 u1 u2 ... uN−1] according to the following:

The output after encoding d = [d0 d1 d2 ... dN−1] is obtained by d = uGN. The encoding is performed in GF(2). < 38.212-Table 5.3.1.2-1: Polar sequence Q0Nmax−1 and its corresponding reliability W(QiNmax) >

The provided images outline the final stages of the 5G NR Polar encoding process, specifically focusing on sub-channel classification, parity bit placement, and the final mathematical transformation into a codeword. 1. Sub-channel Reliability and Parity PlacementThis stage determines which bit indices will carry data and where special parity check (PC) bits should be placed to improve decoding performance.

Parity Check (PC) Placement: If nPC > 0, parity bits are distributed into two groups within the Q̄IN set:

2. Codeword Generation LogicThis stage describes the algorithm to construct the input vector u and calculate the final output bits d.

Example 1 >To visualize how the Generator Matrix (GN) is constructed, we use the Kronecker power (⊗) of the base kernel matrix G2. 1. The Base Kernel (G2) The fundamental building block for all Polar codes in 5G NR is the 2 × 2 matrix:

G2 =

2. Building G4 (N = 4) To get the matrix for N = 4, we take the Kronecker product of G2 with itself (G2 ⊗ G2):

G4 =

3. Building G8 (N = 8) For N = 8, we repeat the process (G2 ⊗ G4). This creates a nested, fractal-like structure:

G8 =

Why this structure matters

The Final Codeword Calculation Once you have your input vector u (which contains your data, parity bits, and zeros for frozen bits), the final output d is simply: d = u · GN (mod 2) Each bit di in the final codeword is an XOR combination of specific input bits in u.

Example 2>Let's apply the NR Polar Encoding logic to a concrete example. We will encode a small 2-bit message (K = 2) into a 4-bit mother code (N = 4). 1. The Inputs

2. Constructing Vector u We need to fill the 4 positions of u = [u0, u1, u2, u3]. Since K = 2, we pick the 2 most reliable indices for data and freeze the rest.

Vector u = [0, 0, 1, 0] 3. The Transformation (d = u · G4) Now we multiply our vector u by the G4 matrix we constructed earlier using binary (XOR) arithmetic:

d = [0, 0, 1, 0] ·

Calculating each bit of d:

Final Codeword d = [1, 0, 1, 0] Summary of the result The message "10" was transformed into the codeword "1010".

Reference[1] 3GPP TSG RAN WG1 #86 - R1-166414 Discussion on LDPC codes for NR [2] 3GPP TSG RAN WG1 #86 R1-166769 Discussion on Length-Compatible Quasi-Cyclic LDPC Codes [3] 3GPP TSG RAN WG1 #86 R1-166770 Discussion on Rate-Compatible Quasi-Cyclic LDPC Codes [4] 3GPP TSG RAN WG1 #86 R1-166929 LDPC Code Design for NR [6] 3GPP TSG RAN WG1 #86 R1-167889 Design of Flexible LDPC Codes

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||