|

|

||

|

A dopamine pathway is a series of connected neurons that use dopamine as the primary neurotransmitter. It is not a single wire or a single function. It is a chain of many neurons passing signals from one region of the brain to another. The key point is that dopamine is the main chemical messenger in those synapses. This is why the pathway gets its name. The brain is not made of isolated modules that work like mechanical blocks. It is a massive web of interconnections. Each neuron can connect to thousands of other neurons. Signals pass through these connection points, called synapses. When signals propagate across a group of neurons that consistently work together for a particular function, we call that group a neural pathway. The identity of the pathway often depends on the neurotransmitter that carries the signal through most of its synapses. Dopamine pathways are one of these specialized circuits. They form long-distance routes from dopamine-producing regions in the midbrain to various target regions such as the striatum, cortex, and limbic structures. Along these routes, dopamine shapes learning, motivation, movement control, and value prediction. The presence of dopamine in the synapses makes the entire pathway sensitive to reward prediction, error signals, and reinforcement-based adaptation. This is what makes dopamine pathways so central to our behavior and our internal models of the world. There are many other types of neural pathways, each defined by different neurotransmitters and different functions. Some rely on serotonin, some on norepinephrine, some on acetylcholine, and many more. Each of them plays a unique regulatory role, and they often interact with one another. But in this note, the focus is on dopamine pathways, because they are deeply involved in motivation, learning by prediction error, motor regulation, and many forms of adaptive behavior. Understanding dopamine pathways helps clarify why dopamine-related processes are complex and multi-layered. The pathway is not just about feeling good. It is about how the brain evaluates outcomes, updates expectations, and adjusts future actions. This perspective gives a more realistic view of how dopamine works across different regions of the brain and why it influences so many aspects of our daily behavior.

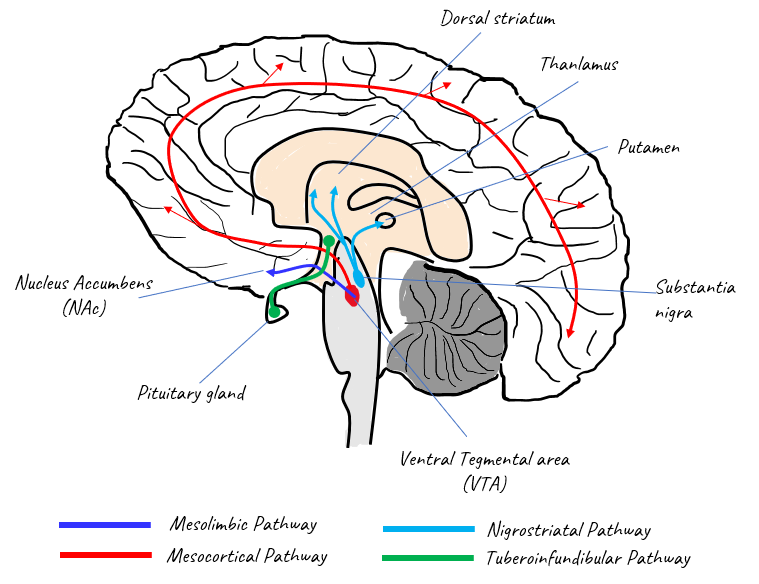

OverviewDopamine pathways are some of the most important long-range circuits in the human brain. They connect deep midbrain nuclei to large areas of the cortex, limbic system, and basal ganglia. Each pathway carries dopamine as the main neurotransmitter, so the signals flowing through the circuit carry the characteristic properties of dopamine: reward prediction, motivation control, reinforcement learning, and fine-tuning of movement. These pathways form the backbone of how the brain evaluates outcomes and adjusts behavior over time. The brain is not built from isolated functional blocks. It operates through dense networks of neurons, and these neurons communicate through synapses using chemical messengers. When many neurons link together to perform a consistent functional role, the result becomes a neural pathway. Dopamine pathways are a specific class of these circuits. Their defining feature is that dopamine is the dominant signal at the synapses along the route. This gives the pathway a particular computational style based on prediction error, motivation regulation, and action selection. There are several well-known dopamine pathways, usually grouped into four or five major circuits. Each pathway supports a slightly different aspect of brain function. Some pathways are involved in executive thinking and decision making. Some influence cognition and working memory. Some regulate reward, desire, and reinforcement. Others control voluntary movement. These circuits overlap and interact, so dopamine never acts in isolation. It works through networks that span multiple regions.

There are multiple dopamine pathways (4 or 5 well known pathways) which are involved in functions as follows.

I personally interested in 'reward and pleasure' part and that is why I decided to write a note for domapine pathway. However, 'reward and pleasure' is only one of several pathways mediated by dopamine and you may have different interest on your own. Well known dopamine pathways are illustrated as below.

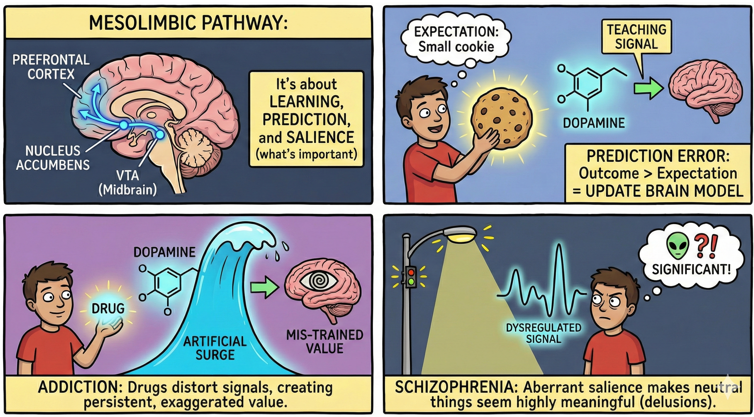

Mesolimbic Dopamine PathwaysThe mesolimbic dopamine pathway is one of the major dopamine circuits that start from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in the midbrain and project to several key regions, most notably the nucleus accumbens, the olfactory tubercle, parts of the amygdala, and sections of the prefrontal cortex. This pathway is often associated with reward-related processing, but the actual mechanism is more about learning, prediction, and the assignment of value rather than simply generating pleasure. The pathway sends dopamine signals when an outcome is better or worse than expected, and this signal updates the brain’s internal model of what is worth paying attention to in the future. When an organism encounters something significant, whether it is food, social interaction, novelty, or a surprising event, the mesolimbic pathway can show increased dopamine activity. This activity does not guarantee pleasure. Instead, it indicates that the event carries information that is relevant for learning or future behavior. The nucleus accumbens is one of the main targets of this signal. Dopamine release here adjusts motivation, energy for action, and reinforcement strength. This means the mesolimbic pathway is involved in shaping habits and guiding choices, not in delivering a direct “pleasure sensation.” This pathway also contributes to several psychiatric and neurological conditions, but again the mechanism is through altered learning signals or disrupted value processing, not through pleasure alone. Drugs of abuse strongly activate the mesolimbic pathway, but the critical point is that they distort prediction-error signals. They produce dopamine surges that do not match real-world outcomes, which mis-trains the system. This distortion is one reason addictive behaviors become persistent, because the brain keeps updating the “value” of the drug far beyond what would happen with natural stimuli. Abnormal activity in the mesolimbic pathway is also implicated in conditions such as schizophrenia. In this case, the issue is not excessive pleasure but dysregulated signaling. Too-strong or poorly timed dopamine signals can make neutral or irrelevant stimuli seem highly significant or meaningful. This misassignment of salience is one explanation for hallucinations and delusional interpretations. Reduced or flattened dopamine signaling in related circuits can also contribute to apathy, reduced motivation, and difficulty initiating action. The mesolimbic dopamine pathway therefore plays a central role in how the brain evaluates significance, assigns motivational weight, and updates learning. It is not a “pleasure pathway.” It is a prediction, reinforcement, and salience pathway. Understanding it in this more accurate way prevents common myths and provides a clearer view of how dopamine supports both healthy behavior and the symptoms seen in various disorders.

The characteristics of this pathway

Conditions that may cause problems in this pathway :

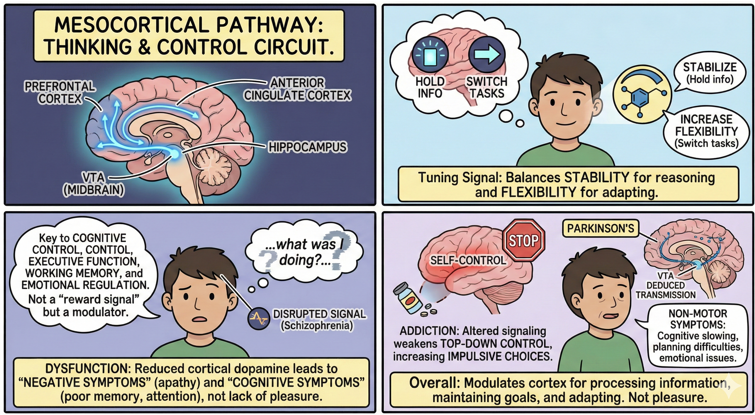

Mesocortical Dopamine PathwaysThe mesocortical dopamine pathway is a major circuit that begins in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain and projects to several higher-order brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and parts of the hippocampal formation. This pathway is closely linked to cognitive control, executive function, working memory, emotional regulation, and the ability to evaluate complex choices. Dopamine signals in this pathway do not act as a “reward signal.” Instead, they modulate how the cortex maintains information, updates decisions, and regulates attention. Dopamine arriving in the prefrontal cortex works differently from dopamine arriving in the nucleus accumbens. In the cortex, dopamine acts more like a tuning signal. It stabilizes neural activity when the brain needs to hold information in mind, and it increases flexibility when the brain needs to switch tasks or re-evaluate a choice. This balance supports reasoning, planning, impulse control, and emotional adjustment. The anterior cingulate cortex uses dopamine signals to monitor conflict, detect errors, and prioritize goals. The hippocampus uses dopamine to tag certain events as important for long-term memory formation. Dysfunction in the mesocortical dopamine pathway is implicated in several psychiatric conditions, especially those involving deficits in executive function. In schizophrenia, reduced or disrupted dopamine signaling in the prefrontal cortex is one proposed mechanism behind negative symptoms such as apathy, reduced initiation of behavior, and diminished emotional expression. Impaired dopamine modulation here is also associated with cognitive symptoms such as poor working memory, reduced attention, and difficulty with complex reasoning. These effects arise from unstable or inefficient cortical circuits, not from changes in “pleasure.” Drug addiction also affects the mesocortical pathway, but the mechanism is indirect. Repeated drug exposure alters dopamine signaling not only in mesolimbic regions but also in cortical circuits that regulate planning and self-control. This can weaken the ability to evaluate long-term consequences and strengthen impulsive choice patterns. The dysfunction does not come from dopamine creating pleasure. It comes from distorted learning signals and reduced top-down control. The mesocortical pathway is not the primary pathway affected in Parkinson’s disease, but it can still be involved. Parkinson’s disease is mainly caused by degeneration of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra, which primarily affects the nigrostriatal pathway and leads to motor symptoms. However, VTA neurons can also degenerate to some degree, resulting in reduced dopamine transmission to the prefrontal cortex. This reduction contributes to cognitive slowing, reduced planning ability, and difficulties with emotional regulation. These are sometimes referred to as “non-motor symptoms” of Parkinson’s disease. Overall, the mesocortical dopamine pathway is essential for higher-order thinking and emotional balance. It does not produce pleasure or reward. Instead, it modulates how the cortex processes information, maintains goals, and adapts to new conditions. Understanding this pathway clarifies why dopamine plays such diverse roles across different brain regions and why disruptions here can result in cognitive and emotional symptoms rather than changes in reward experience.

The characteristics of this pathway

Conditions that may cause problems in this pathway :

Nigrostriatal Dopamine PathwaysThe nigrostriatal dopamine pathway is one of the core motor-control circuits in the brain. It begins in the substantia nigra pars compacta, a dopamine-producing region in the midbrain, and projects to the dorsal striatum, which includes the caudate nucleus and putamen. This pathway does not create pleasure signals. It primarily modulates how the basal ganglia initiate, coordinate, and smoothly execute voluntary movements. The substantia nigra sends dopamine to the striatum to adjust the activity of two major motor circuits known as the direct and indirect pathways. Dopamine does not “cause movement” directly. Instead, it fine-tunes the balance between facilitating desired movements and suppressing unwanted or competing movements. The striatum uses dopamine to regulate signal flow, timing, and the gain of these circuits. Small changes in dopamine levels can shift how easily a movement can be started or how precisely it can be controlled. Dopamine receptors in the striatum (mainly D1 and D2 receptors) respond differently, and this dual-receptor system allows dopamine to selectively enhance or reduce the activity of specific neural populations. Through this mechanism, the nigrostriatal pathway provides the modulatory control that makes smooth, intentional movement possible. Without this modulation, movements become slow, rigid, or unstable. Damage to the dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra is the central cause of Parkinson’s disease. As these neurons degenerate, dopamine levels in the dorsal striatum drop sharply. With reduced dopamine, the direct and indirect pathways fall out of balance. Movements become harder to initiate, muscle stiffness increases, and tremors may appear. These symptoms arise from disrupted motor-circuit regulation rather than from a general lack of motivation or energy. The degeneration also affects other related pathways to varying degrees, contributing to non-motor symptoms such as slowed thinking or mood changes. The nigrostriatal pathway therefore plays a foundational role in motor control. It ensures that voluntary movement is timely, coordinated, and efficient. When dopamine signaling in this pathway becomes impaired, the result is profound motor dysfunction, which is why the pathway is central to understanding disorders like Parkinson’s disease and the physiological basis of movement in general.

The characteristics of this pathway

Conditions that may cause problems in this pathway :

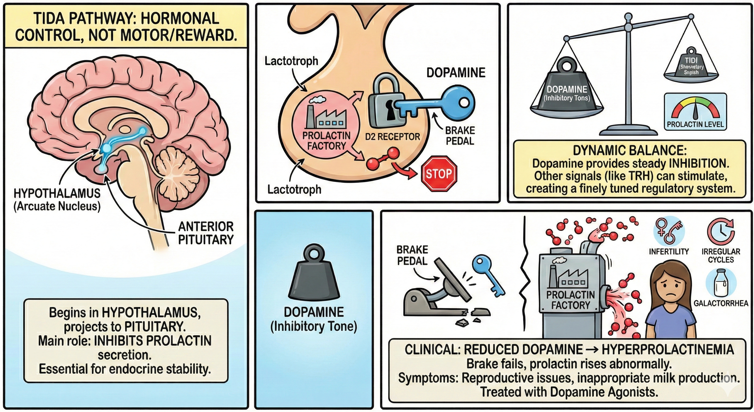

Tuberoinfundibular Dopamine PathwaysThe tuberoinfundibular dopamine pathway (TIDA) is a specialized dopamine circuit that begins in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus and projects toward the anterior pituitary gland. Unlike other dopamine pathways, the TIDA pathway does not regulate movement, reward, or cognition. Its main role is hormonal control. Dopamine released by these hypothalamic neurons acts as the primary inhibitor of prolactin secretion from the pituitary gland. Prolactin is a hormone involved in lactation, reproductive physiology, immune modulation, and several growth-related processes. Under normal conditions, the pituitary continuously receives dopamine from TIDA neurons, which suppresses prolactin release through D2 receptors on lactotroph cells. This means dopamine functions as the “brake” in the prolactin system. When dopamine levels drop, prolactin secretion increases. When dopamine levels rise, prolactin secretion decreases. The system is dynamic and forms a homeostatic loop between the hypothalamus and pituitary. The balance between dopamine and prolactin is influenced by other hypothalamic signals. For example, thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) can stimulate prolactin release, while dopamine opposes this effect. This creates a finely tuned regulatory system where the TIDA pathway provides ongoing inhibitory tone, and other hormones provide context-dependent adjustments. Clinical conditions illustrate the importance of this pathway. When dopamine production or receptor signaling in the TIDA pathway is reduced, prolactin levels can rise abnormally. This condition, called hyperprolactinemia, can lead to symptoms such as infertility, irregular menstrual cycles, low libido, and inappropriate milk production (galactorrhea). Dopamine agonist medications, which activate D2 receptors, are commonly used to restore the inhibitory signal and reduce prolactin levels. The TIDA pathway is therefore essential for endocrine stability. It shows that dopamine is not only involved in brain circuits for movement or motivation, but also functions as a hormone-regulating signal in the hypothalamus–pituitary axis. Understanding this pathway highlights the broad physiological roles of dopamine across neural and endocrine systems.

The characteristics of this pathway

Conditions that may cause problems in this pathway :

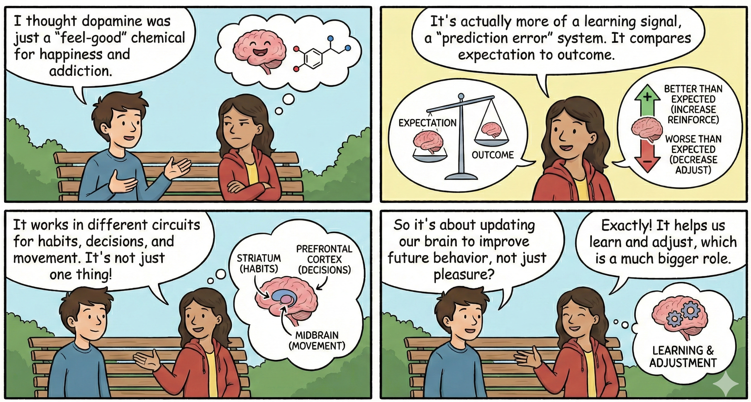

Myth about DopamineMany people describe dopamine as the “feel-good chemical,” but this is only a small part of what dopamine really does. The deeper mechanism is very different. Dopamine acts more as a learning signal. It works by comparing what you expect and what you actually get. So it increases when the outcome is better than expected, and it decreases when the outcome is worse than expected. This is a prediction-error system. This mechanism trains the brain. It adjusts future behavior. It updates choices. It fine-tunes habits. This learning process is the fundamental reason behind many behaviors that people mistakenly attribute to simple “pleasure.” Another big reason behind the myths is oversimplification. People often reduce a multi-layer biological process into a single phrase. They say dopamine equals pleasure. They say more dopamine equals more happiness. They say high dopamine equals addiction. These are inaccurate or incomplete. Dopamine works in multiple circuits. Dopamine in the striatum shapes habits and reinforcement. Dopamine in the prefrontal cortex regulates decisions and working memory. Dopamine in the midbrain modulates movement. Each circuit has different receptor types, different time scales, and different roles. So the same molecule behaves differently depending on the circuit. The over-simplified idea creates many misunderstandings. It leads to the belief that dopamine is only about pleasure. It leads to the belief that dopamine spikes automatically create addiction. It leads to the belief that low dopamine always means low motivation. These interpretations ignore the actual mechanism. Dopamine is not a direct “reward chemical.” It is a signal that updates internal models. It teaches the brain what is better than expected, what is worse than expected, and what should be repeated or avoided. It operates like a feedback controller in engineering, so it adjusts the system based on errors between expectation and outcome. When we understand dopamine in this way, many myths fade away. Dopamine is not about constant pleasure. It is about constant learning. It does not simply make you feel good. It teaches you what mattered, and how much. It shapes your behavior over time. It is dynamic, context-dependent, and always interacting with other neurotransmitters. A more accurate view is that dopamine supports prediction, adjustment, and improvement rather than continuous happiness. This perspective makes the complex stories around dopamine much clearer and removes the common myth that dopamine alone drives our behavior.

Myth 1: Dopamine is the "happiness" neurotransmitterMyth 2: Dopamine is the "addiction chemical"Myth 3: More dopamine equals better mental performanceMyth 4: Dopamine is only involved in pleasurable experiencesMyth 5: Dopamine is only related to tangible rewards like food or moneyMyth 6: Dopamine is responsible for the immediate pleasure of achieving goalsMyth 7: Dopamine can be "reset" or "detoxed" by fasting or abstaining from pleasureMyth 8: Dopamine is only released during enjoyable experiencesMyth 9: Dopamine is only responsible for reward-seeking behaviorMyth 10: Dopamine makes us perform specific behaviorsMyth 11: Dopamine causes instant gratificationMyth 12: Dopamine is directly responsible for addictionReference

YouTube

|

||