|

|

||

|

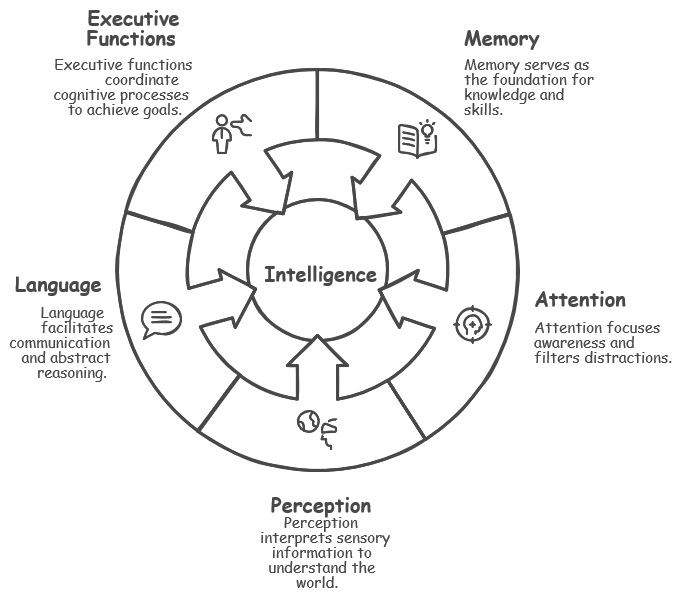

From a neuroscience perspective, intelligence is a multifaceted phenomenon that encompasses a wide array of cognitive processes and abilities. It is not a singular trait, but rather a complex interplay of neural mechanisms that enable the brain to learn new information, reason through complex problems, find creative solutions, adapt to changing circumstances, and grasp abstract ideas. Intelligence involves the integration of various cognitive functions, including memory, attention, perception, language, and executive functions like planning and decision-making. These processes are supported by intricate neural networks that span different regions of the brain, with each region contributing unique computational capabilities.

Cognitive Functions Underpinning IntelligenceRather than being a single attribute, Intelligence is a diverse construct that allows the brain to acquire knowledge, think critically, solve challenges, adapt to changes, and understand abstract ideas. This sophisticated coordination of neural mechanisms depends on multiple cognitive functions, each providing distinct computational skills that enhance intelligent behavior. The integration of these cognitive functions, supported by intricate neural networks and shaped by experience and learning, gives rise to the multifaceted phenomenon of intelligence. By understanding the neural mechanisms underlying these cognitive processes, we can gain valuable insights into how the brain generates intelligent behavior and develop interventions to enhance cognitive function and unlock the full potential of the human mind.

Memory: The Cornerstone of IntelligenceMemory plays a fundamental role in intelligence, serving as the repository of knowledge, experiences, and skills that shape our understanding of the world and guide our actions. It encompasses two primary systems: Working Memory: The Mental WorkspaceWorking memory is a dynamic and flexible system that acts as a mental workspace, allowing us to temporarily hold and manipulate information in the mind. It is essential for a wide range of cognitive processes, including:

The capacity of working memory is limited, and information is typically retained for only a short period. However, through active rehearsal and manipulation, information can be transferred to long-term memory for more permanent storage. Long-Term Memory: The Knowledge RepositoryLong-term memory is a vast and durable storage system that retains information over extended periods, from minutes to a lifetime. It serves as the repository of our knowledge, experiences, and skills, enabling us to learn, adapt, and thrive in our environment. Long-term memory is essential for:

The capacity of long-term memory is virtually unlimited, and information can be stored in various formats, including semantic memory (facts and concepts), episodic memory (personal experiences), and procedural memory (skills and habits). Together, working memory and long-term memory form a powerful cognitive duo, enabling us to process information, learn from experience, and make informed decisions. The interplay of these two memory systems is crucial for intelligent behavior, and their efficient functioning is essential for cognitive health and well-being. Attention: The Spotlight of the MindAttention is the cognitive process that allows us to focus our awareness on specific stimuli or tasks while filtering out irrelevant information. It acts as a spotlight, illuminating the most salient aspects of our environment and guiding our thoughts and actions. Attention is crucial for efficient information processing, decision-making, and goal-directed behavior. There are two primary types of attention: Selective Attention: The Filter of FocusSelective attention is the ability to focus on a specific stimulus or task while ignoring distractions. It acts as a filter, allowing relevant information to enter our conscious awareness while blocking out irrelevant or competing stimuli. This ability is essential for:

Divided Attention: The Multitasking MaestroDivided attention is the ability to allocate attentional resources to multiple tasks simultaneously. It allows us to juggle different demands and engage in multitasking activities, such as driving while talking on the phone or listening to a lecture while taking notes. However, divided attention has limitations:

The ability to effectively allocate attentional resources is crucial for navigating the complexities of modern life, where we are constantly bombarded with information and demands. However, it is important to be mindful of the limitations of divided attention and prioritize tasks that require focused concentration for optimal performance and safety. Perception: The Gateway to UnderstandingPerception is the process through which we acquire information about the world around us and make sense of our experiences. It involves the intricate interplay of sensory input, neural processing, and cognitive interpretation, allowing us to construct a meaningful representation of our environment. Two key aspects of perception are: Sensory Perception: The Raw Data of ExperienceSensory perception is the process of receiving and interpreting information from our senses. It involves the detection of stimuli through specialized sensory receptors, the transmission of neural signals to the brain, and the initial processing of this information in sensory cortices. Our senses provide us with a wealth of information about the world, including:

Sensory perception provides the raw data of experience, which is then further processed and interpreted by higher-order cognitive functions. Pattern Recognition: Making Sense of the WorldPattern recognition is the ability to identify meaningful patterns and regularities in sensory information. It involves the organization and categorization of sensory input, allowing us to identify objects, recognize faces, understand language, and make predictions about future events. Pattern recognition is essential for:

Pattern recognition is a complex process that involves both bottom-up processing (driven by sensory input) and top-down processing (guided by prior knowledge and expectations). The interplay of these processes allows us to construct a coherent and meaningful understanding of the world around us. Language: The Bridge of Communication and ThoughtLanguage is a uniquely human cognitive faculty that enables us to communicate our thoughts, feelings, and ideas with others. It serves as a bridge between individuals, facilitating social interaction, collaboration, and the transmission of knowledge across generations. Language is also deeply intertwined with thought, shaping our understanding of the world and enabling us to reason abstractly and creatively. Two essential aspects of language are: Verbal Comprehension: Understanding the World Through WordsVerbal comprehension is the ability to understand spoken and written language. It involves decoding the meaning of words, sentences, and discourse, extracting relevant information, and integrating it with prior knowledge. This ability is essential for:

Verbal Fluency: Expressing Ourselves with EloquenceVerbal fluency is the ability to produce language fluently and expressively. It involves retrieving words from memory, constructing grammatically correct sentences, and articulating thoughts in a clear and coherent manner. This ability is crucial for:

The interplay of verbal comprehension and verbal fluency allows us to navigate the complexities of human communication and engage in meaningful social interactions. Language is a powerful tool that shapes our thoughts, emotions, and perceptions, and its mastery is a key component of human intelligence. Executive Functions: The Conductor of Cognitive OrchestraExecutive functions are a set of higher-order cognitive processes that regulate and coordinate other cognitive functions and behaviors. They act as the conductor of the cognitive orchestra, orchestrating the complex interplay of attention, memory, perception, and language to achieve goals and adapt to changing environments. Three key executive functions are: Planning: The Architect of ActionPlanning is the ability to set goals, develop strategies, and organize actions to achieve desired outcomes. It involves:

Planning is essential for complex tasks that require coordination and foresight, such as writing a research paper, managing a project, or navigating a new city. Decision-Making: The Compass of ChoiceDecision-making is the ability to evaluate options, weigh the risks and benefits of each choice, and select the most appropriate course of action. It involves:

Decision-making is a complex process that is influenced by various factors, including emotions, biases, and social context. However, it is a critical skill for navigating the challenges of life and achieving personal and professional success. Inhibitory Control: The Guardian of Self-RegulationInhibitory control is the ability to suppress irrelevant impulses and inhibit inappropriate responses. It involves:

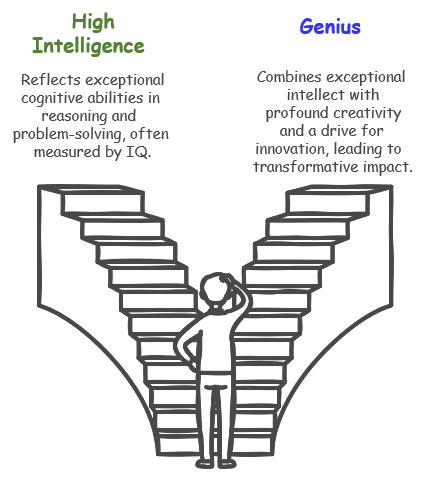

Inhibitory control is essential for goal-directed behavior, as it allows us to resist temptations, delay gratification, and focus on the task at hand. It is also crucial for social interactions, as it enables us to control our emotions and behaviors in accordance with social norms and expectations. Together, planning, decision-making, and inhibitory control form a powerful cognitive trio, enabling us to navigate complex environments, achieve our goals, and adapt to changing circumstances. The development and refinement of these executive functions are key components of human intelligence and well-being. High Intelligence vs. Genius: A Distinction with a DifferenceWhile high intelligence and genius are frequently mentioned in the same breath, it's important to recognize that they are not synonymous. Both terms pertain to exceptional cognitive abilities, but they represent distinct points on the spectrum of human intellect.

The distinction between high intelligence and genius lies in the realm of creativity and impact. While highly intelligent individuals may possess exceptional problem-solving skills and the ability to master complex information, geniuses are driven by a burning curiosity and a relentless pursuit of knowledge. They are not content with simply understanding existing concepts; they seek to expand the boundaries of human knowledge and create something truly novel. Moreover, genius is often associated with a certain level of unconventionality. Geniuses may challenge societal norms, defy expectations, and pursue unconventional paths in their quest for knowledge and innovation. Their ideas may be met with skepticism or even ridicule initially, but their unwavering determination and unique perspective ultimately lead to transformative breakthroughs. In conclusion, while high intelligence is a remarkable trait that enables individuals to excel in various domains, genius represents a rare and exceptional form of intellect that combines exceptional cognitive abilities with profound creativity and a drive to make a lasting impact on the world. Genius and Savant Syndrome: Unveiling the Nuances of Exceptional AbilitiesThe terms "genius" and "savant syndrome" are often used interchangeably in popular culture, both referring to individuals who possess extraordinary talents or abilities that seem to defy conventional understanding. However, a closer examination reveals significant differences in their cognitive profiles and the nature of their exceptional skills. Genius: A Multifaceted BrillianceGenius is a term used to describe individuals who exhibit exceptional intellectual or creative prowess. These individuals often demonstrate a profound understanding and mastery of their chosen field, coupled with an uncanny ability to generate novel ideas and solutions to complex problems. Geniuses are not merely intelligent; they possess a unique blend of cognitive abilities, including exceptional memory, keen observation skills, abstract reasoning, and divergent thinking. Their contributions often revolutionize fields of knowledge, challenge existing paradigms, and leave a lasting impact on society. Savant Syndrome: Islands of GeniusSavant syndrome, on the other hand, is a rare condition characterized by the presence of extraordinary abilities in specific domains, such as music, art, mathematics, or calendar calculation, despite significant cognitive impairments or developmental disabilities. Individuals with savant syndrome often exhibit a narrow focus on their area of expertise, with a remarkable ability to memorize and process information related to their specific talent. However, their exceptional skills are often accompanied by challenges in other areas of cognitive functioning, such as social interaction, communication, and adaptive skills. Key Differences and SimilaritiesWhile both genius and savant syndrome are associated with exceptional abilities, several key differences distinguish them:

Despite these differences, both geniuses and savants share a common thread of exceptional abilities that challenge our understanding of human potential. They serve as a reminder of the vast and diverse capabilities of the human mind and the importance of recognizing and nurturing individual talents, regardless of their cognitive profile. Reference

YouTube

|

||