|

|

||

|

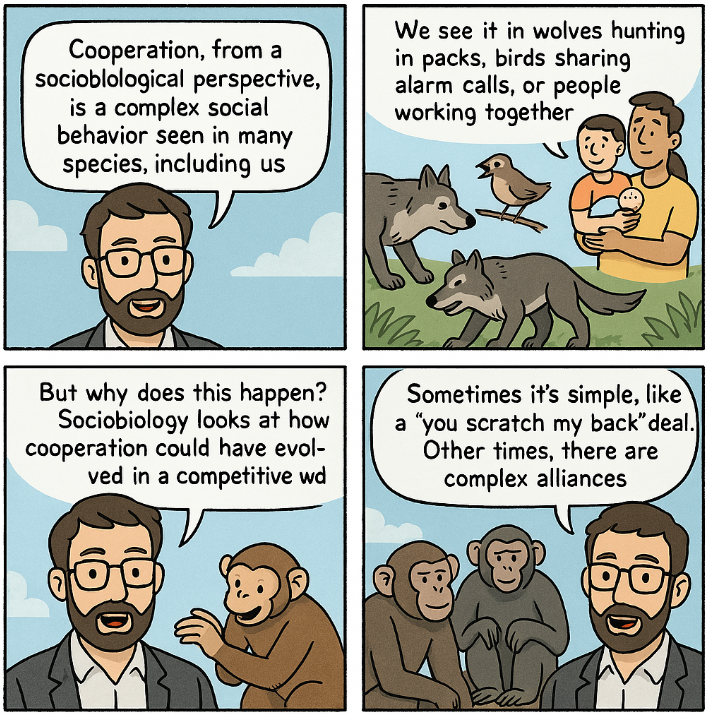

Cooperation, from a sociobiological perspective, is a complex social behavior observed in many species, including humans, where individuals work together to achieve a common goal. It is a fundamental aspect of social organization and can take various forms, ranging from simple mutualism to complex alliances and coalitions. Cooperation might seem like a no-brainer--something we just do because it feels right. But from a sociobiological perspective, it's actually a surprisingly deep and complex behavior. Across the animal kingdom, and especially in humans, we see individuals working together--whether it’s wolves hunting in packs, birds sharing alarm calls, or people teaming up for everything from raising families to launching rockets into space. But why does this happen? Sociobiology dives into that question, asking how cooperation could have possibly evolved in a world shaped by competition. It looks at how helping others--even when there's a cost--can still make sense in terms of survival and reproduction. Sometimes cooperation is simple, like a "you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours" deal. Other times, it involves intricate alliances and social rules. What fascinates researchers is not just that we cooperate, but how those cooperative instincts got built into our biology over millions of years—and what they reveal about the hidden rules of nature that hold social life together.

Sociobiology seeks to understand the evolutionary origins and mechanisms underlying cooperative behavior. It explores how cooperative strategies have evolved over time through natural selection, and how they contribute to the survival and reproductive success of individuals and groups. Why do we risk ourselves to help others in a world built on survival?Why do we risk ourselves to help others in a world built on survival? At first glance, cooperation seems like a beautiful and intuitive part of life—parents caring for children, strangers offering help, animals grooming one another. But from an evolutionary standpoint, it's a puzzling behavior. Natural selection is often seen as favoring those who maximize their own chances of survival and reproduction, not those who sacrifice time, energy, or safety for someone else. So why does cooperation exist at all? This question lies at the heart of sociobiology, which seeks to understand how seemingly selfless behaviors could have evolved in a world shaped by competition. The answer, as it turns out, reveals not only the hidden logic of evolution but also something profound about the roots of morality, society, and what it means to be human. Now let's think a little bit deepr into why sociobiologists care to reach on this kind of seemingly natural behavior.

Sociobiological Explanations for Cooperative BehaviorSociobiology provides a unique framework for understanding the complexities of cooperative behavior across different species. It seeks to unravel the evolutionary mechanisms that have shaped the diverse forms of cooperation observed in nature, including altruism, mutualism, and reciprocal exchange. Several key theories and concepts, such as kin selection, reciprocal altruism, group selection, and mutualism, offer complementary explanations for how cooperative behaviors can arise and persist within a population. These theories consider the costs and benefits associated with cooperation, the role of relatedness and reciprocity, and the potential for group-level selection to favor cooperative traits. By exploring these diverse mechanisms, sociobiology sheds light on the intricate interplay between individual interests and collective benefits that ultimately drive the evolution and maintenance of cooperative behavior in the natural world. Kin Selection:This theory posits that individuals are more likely to cooperate with relatives because they share genes. By helping kin, individuals indirectly promote the survival of their own genes, even if it comes at a personal cost. This explains many instances of cooperation among close relatives, such as parental care or sibling support. Kin selection theory provides a compelling explanation for the widespread prevalence of cooperation among close relatives in both human and non-human animal societies. The theory posits that individuals are inherently more inclined to help their relatives because they share a significant proportion of their genetic material. By assisting their kin, individuals are indirectly increasing the chances of their own genes being passed on to future generations, thus enhancing their overall evolutionary fitness. This seemingly altruistic behavior, where individuals sacrifice their own well-being for the benefit of their relatives, is driven by the underlying principle of inclusive fitness. Inclusive fitness considers not only an individual's direct reproductive success (the number of offspring they produce) but also the reproductive success of their relatives, weighted by the degree of relatedness. In other words, helping a close relative, such as a sibling or offspring, can be just as beneficial, from an evolutionary perspective, as producing one's own offspring. Kin selection theory provides a powerful framework for understanding the evolution of cooperation and altruism, highlighting the fundamental role of genetic relatedness in shaping social behavior across diverse species. Examples of Kin Selection in Non-Human Animals:

Examples of Kin Selection in Humans:

Reciprocal Altruism:This concept suggests that cooperation can evolve even among non-relatives if there is a mutual expectation of future benefits. Individuals may help others with the understanding that the favor will be returned later, creating a system of reciprocal exchange that benefits both parties over time. The concept offers a compelling explanation for the emergence of cooperation among unrelated individuals, a phenomenon that transcends species boundaries and permeates various social structures. This concept posits that cooperation can flourish when individuals engage in mutually beneficial exchanges, with the expectation that favors will be returned in the future. This reciprocal exchange forms the foundation of a sustainable cooperative system where both parties reap benefits over time. Examples of Reciprocal Altruism in Non-Human Animals:

Examples of Reciprocal Altruism in Humans:

Group Selection:This theory proposes that cooperation can evolve if it benefits the group as a whole, even if it may be disadvantageous to some individuals within the group. Groups with higher levels of cooperation may outcompete less cooperative groups, leading to the spread of cooperative traits in the population. This theory offers a unique perspective on the evolution of cooperation by highlighting the importance of collective benefits over individual gains. It posits that cooperative behaviors can emerge and thrive in a population even if they are not directly advantageous to every individual within the group. Instead, the driving force behind the evolution of cooperation lies in the enhanced survival and reproduction of groups that exhibit higher levels of cooperation compared to their less cooperative counterparts. The central idea is that groups, rather than individuals, can be considered as units of selection. When groups compete for resources, territory, or mates, those with a higher prevalence of cooperative individuals often gain a competitive edge. Cooperation enables groups to accomplish tasks that would be challenging or impossible for individuals acting alone, such as defending against predators, acquiring food, or raising offspring. As a result, groups with more cooperative members tend to thrive and expand, while less cooperative groups may decline or even face extinction. This process of differential survival and reproduction ultimately leads to the spread of cooperative traits throughout the population, even if these traits might not directly benefit every individual within the group. By emphasizing the importance of group-level benefits, group selection theory provides a compelling explanation for the evolution of cooperation in diverse species, including humans. While the theory has faced criticism and debate, it remains a valuable tool for understanding the complex interplay between individual and collective interests in the development of cooperative behaviors. Examples of Group Selection in Non-Human Animals:

Examples of Group Selection in Humans:

MutualismThis form of cooperation involves a mutually beneficial relationship between different species, where both parties gain from the interaction. Examples include cleaner fish removing parasites from larger fish or bees pollinating flowers while collecting nectar. Mutualism exemplifies a remarkable form of cooperation that transcends species boundaries, where two or more distinct organisms engage in a mutually beneficial relationship. This symbiotic interaction is characterized by an exchange of goods, services, or resources that enhances the survival and reproductive success of all parties involved. In essence, mutualism is a win-win scenario where both partners derive advantages from their interactions, fostering a harmonious co-existence within their ecological niche. Examples of Mutualism in Non-Human Animals:

Examples of Mutualism in Humans:

ReferenceYouTube

|

||