|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

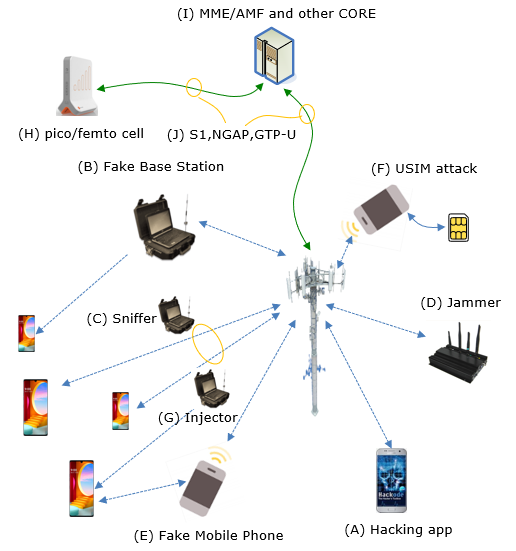

In any information technology, there has always been some risk of security / hacking. But until recently (probably until now) cellular communication is relatively hard (considered impossible to many people) to attack. However, I don't think it is the case any more and it is about the time to start thinking of security issues seriously in cellular communication. Just for short, I can think of several possible points of security volnerability (i.e, points of attack). Of course, there would be more points that I failed to think of and will come out more.

Possible Points of AttacksFor most person, the point (A) (Security Attack by Mobile phone App) would be the most widely known type. But strictly speaking this type of attack would not be classified as security issues on cellular communication itself unless it is hacking the modem chipset or mobile radio protocol. It is more of conventional (?) type of attack that we often hear of for other application like PC etc. Other type of attack that are relatively well known would be point (D). But Jammer can be used not for attack, but for an intended purpose (e.g, blocking culluar communication in workshop hall etc), but this can be considered as a serious attacker if it is blocking (or sometimes even harming directly on hardware of the system). When I am talking about "Security In cellular communication", I would focus more on point (B), (C), (D). These are the main topics in this note.

Here’s a brief description of each attack point in cellular security as illustrated above Why we didn't worry much of Cellular Security ?For some reason, (at least from 3G or later technololgy) cellular communication is almost perfectly secure from any type of security attack. I don't know exactly what is the reasoning behind this perception... I personally would think of a few reason as follows :

Why now we should worry of this ?To me, I haven't see much differences from 3G through 5G in terms of fundamental security protection algorithm. Why we should consider seriously on this issue. What I have seen in terms of security issue is more of changes in environmental changes in accessbility of the technology. Some of those changes that I can think of are as follows.

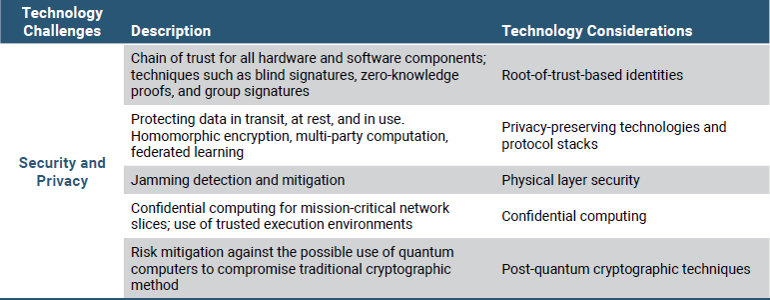

What to expect in Security Protection in next generation (6G) cellular system ?In this section, I will try to compile various ideas and visions proposed by different sources.

Source : Roadmap to 6G (NextG Alliance) Following is some suggestions in 6G whitepaper from SamSung at security point of view.

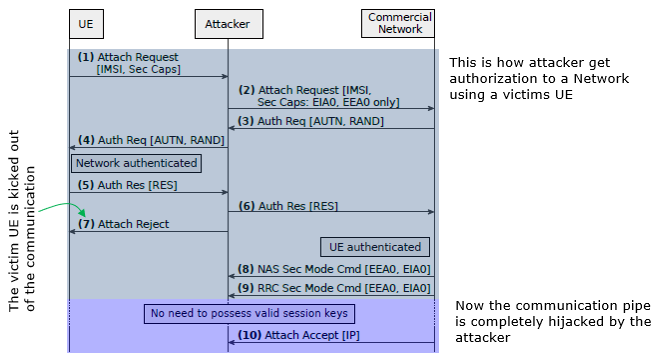

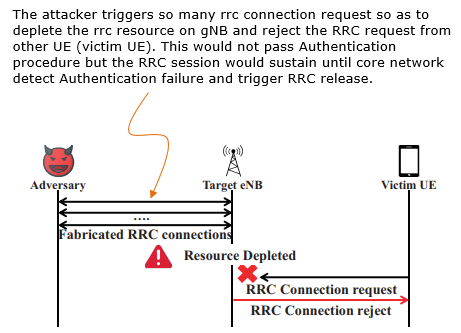

Evolution of Cellular Technology and Coevolution of Attacking StrategyFrom the early days of 1G analog systems to the lightning-fast 5G networks of today, each generation of cellular technology has brought significant advancements in speed, capacity, and reliability. However, as these technologies have evolved, so too have the strategies of those looking to exploit their vulnerabilities. The coevolution of attacking strategies alongside technological progress presents a dynamic landscape where innovation in security must keep pace with technological breakthroughs. here, we explore the intertwined journey of cellular technology advancements and the corresponding evolution of cyberattack methodologies, highlighting the challenges and solutions in this ever-changing digital battlefield. Here, Norbert Ludant has provided a comprehensive and perceptive review on the evolution of security procedures and counteracting methodologies.. Security Vulanerability and Attacking stratgies along with generation of cellular technologyInitially, cellular communications were not very secure because they were designed with the attacker capabilities at that time in mind. For that reason, 2G did not even have mutual authentication, because they didn't think it would be doable for an attacker to actually create a rogue BS. However, with the proliferation of SDRs and low-cost hardware and software implementations, all this became possible. In fact to this day many attacks relied on downgrading a user to insecure 2G networks, and that is why Android for instance now allows the user to disable 2G. Moreover, if you look at the 5G standard, 5G-AKA now has an Anti-Bidding-down Between Architectures (ABBA) parameter to protect from downgrade attacks. Additionally, for instance in 38.331 Annex B.1, Protection of RRC Messages, I think there are indication that they are trying to protect from some of these downgrade attacks, e.g. "RRCRelease message sent before AS security activation cannot include deprioritisationReq, suspendConfig, redirectedCarrierInfo, cellReselectionPriorities information fields." In 3G, 3GPP added mutual authentication, making rogue base stations less effective. However, user tracking is still a very important attack, which was possible both in 3G and 4G networks. In fact, law enforcement used this very often, basically by using IMSI catchers (Stingray). In essence, you can just start a rogue eNB with high power, and when users try to connect to your rogue BS, you would capture their IMSI, or if they send TMSI, you would send an Identity Request with type IMSI. There are various other ways of tracking users, researchers also showed that it is possible to localize users by linking TMSI to social media, phone number, etc, by listening to paging messages, for instance through silent SMS/phone calls. However, in 5G, to fix the issue with user-tracking, the standard added the use of SUCI instead of sending the unprotected IMSI. In this way, it is not possible to implement IMSI catcher in 5G (except in some corner cases). Additionally, now it is also mandatory to change the TMSI after every paging procedure, which makes paging-procedure user tracking attacks also hard to perform. Other protection mechanisms were also added in 5G such as protection of the initial NAS message, or integrity protection of the user plane. Due to all these changes, the 5G RAN is considered quite more secure than its predecessor LTE. Higher layer vs Lower Layer AttackAs mentioned above, there has been significant efforts devoted to enhancing security mechanisms in 5G, and it has become harder and harder to find vulnerabilities in the security protection mechanism at higher layers (e.g, exploitation of security related signaling procedure). Due to this, I think some of the security research may be shifting to study vulnerabilities in devices with low-capabilities (IoT), or unprotected low layers. In general the impact of vulnerabilities scales as you go to higher layers, because there is more persistent or relevant UE-related information being exchanged (e.g. IMSI, encrypted data, etc), however it is also easier to protect with proper security measures. The lower layers are tricky to protect, because there is a strong trade-off between security/privacy/reliability and performance, both in throughput and latency. In general I would say that the lower layers are harder to attack or have a strong impact because everything is less “static”; RRC connections can last for some seconds, which leads to temporary identifiers, whereas higher-layer connections are more persistent. Another aspect of working on the low-layers is that it requires expertise in many tough subjects required for PHY attacks, such as RF knowledge, security, and in-depth understanding of the complicated 3GPP procedures. As an example of security/performance trade-off, due to the requirements for lower-latency communications, many procedures are being pushed to the lower layers, for instance, the initial 4G release had ~7 MAC CE in the specification, whereas the latest 5G release has more than 50. The MAC headers are sent unprotected, because encryption/integrity protection happens at PDCP, so attackers can sniff/inject control elements at low layers nowadays, which is very important too. In my research, the increased security at higher layers, and the push for control in the lower layers, motivated me to analyze the security and privacy of the low layers of the 5G protocol stack. Particularly, as the encryption and integrity protection happen at the PDCP layer, we look for information leakages in the layers below, such as PHY/MAC. Moreover, with new use-cases such as URLLC, the reliability of the system becomes a crucial aspect, thus the standards for protection are raised, and attacks such as DoS become more important. In one of our projects, for instance, we wanted to understand if it is still possible to track users, similarly to IMSI-catching, but in 5G, where all the new security enhancements are in place. To answer that we look at the low layers, at the resource-scheduling happening in the PHY/MAC. We leverage the fact that the RNTI (Radio Network Temporary Identifier) is tied to one RRC Connection, and would remain the same while there is an active connection. Then, we inject specific traffic pattern, and we look at the resources allocated to all users in a cell, if we are able to identify the pattern, then we would be able to tell if a user is in a certain area or not, and link it to the phone number/other high layer ID that we used to generate the traffic. Moreover, we create a modified signal app that sends a message with a wrong Message Authentication Code (MAC). In this way, you can send constant data to a signal app user, without the user receiving any notification, because the messages are discarded upon arrival due to wrong integrity checks. This makes the attack quite stealthy. In general, I think attacks on the signaling level are more powerful, because they can contain long-term user-specific data (identifiers, location...), or modify the state of the UE. However, by looking at the PHY level, we showed that it is also possible to infer user information and violate the user-privacy and track users, finding alternatives for given attacks, and motivating the protection of low-layer information. How to attack ?Don't get me wrong. This is not about to let you know of tricks of attac to be an attacker. This is for illustrating some cases of volnerability and motivating you to get interested in how to improve those volnerability by design. I will also try to summarize what I have learned from various technichs introduced in various sources that I have read and experts who I have personal connection to. Impersonalization AttackI think this is the most well known type of attack. Basically it is hijacking the victim UE and network's authentication and security parameters and manipulate it in such a way that network would apply the lowest level of security mechanism (Authentication only and no integrity protection & Ciphering) and occupay the traffic channel with victim UE's access information.

Source : LTE security disabled: misconfiguration in commercial networks by Chlosta, Merlin et al. The description of this procedure already described in very readable way -:), I am just copying the descrition from the original paper as it is : (1) The benign UE connects to the attacker and sends an Attach Request, containing the IMSI and Security Capabilities. (2) The attacker forwards the Attach Request but modifies the supported algorithms to EIA0 and EEA0 only. (3) The commercial network starts the AKA with an Authentication Request containing the challenge and network authentication (RAND and AUTN). (4) The attacker forwards the Authentication Request to the victim UE. Note that in case the UE connects with Attach Request but identifies with TMSI, the attacker requests the IMSI with an Identity Request. If the UE connects with Service Request or Tracking Area Update, the attacker denies access with reason Implicitly Detached, forcing the UE to re-attach with Attach Request Resource Depletion Attack

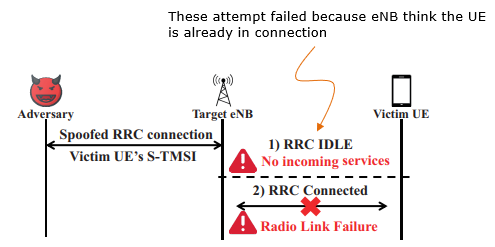

Source : Touching the Untouchables: Dynamic Security Analysis of the LTE Control Plane - Hongil Kim et al Following is the direct citation from the paper linked above : The adversary repeatedly performs Random Access and generates RRC Connections in order to increase the number of active RRC Connections as depicted in the diagram shown above. In a normal situation, immediately after the RRC Connection is established, an initial NAS Connection procedure proceeds through either an NAS Attach request or NAS Service request piggybacked on an RRC Connection complete message. In our attack, the adversary sends the NAS Attach request with an arbitrary user IMSI. Unlike the normal procedure, once the adversary receives the NAS Authentication request, it restarts Random Access to establish a new RRC Connection. The reason the adversary does not reply to the NAS Authentication request from the MME is to sustain the established RRC Connection while the MME waits for a valid NAS Authentication response. If the adversary replies with an invalid NAS Authentication response, it causes immediate RRC Connection release. One consideration for the attack to succeed is that the number of newly established RRC Connections has to be greater than the number of existing RRC Connections that are released. Blind DoS AttackThis attack prevents the Network from sending paging to the victim UE or cause Radio Link Failure by continuously triggering RRC Connection with the victim's S-TMSI.

Source : Touching the Untouchables: Dynamic Security Analysis of the LTE Control Plane - Hongil Kim et al For this kind of attack, the attacker should figure out Victim's S-TMSI first. How ? This is the quote from the paper linked above.

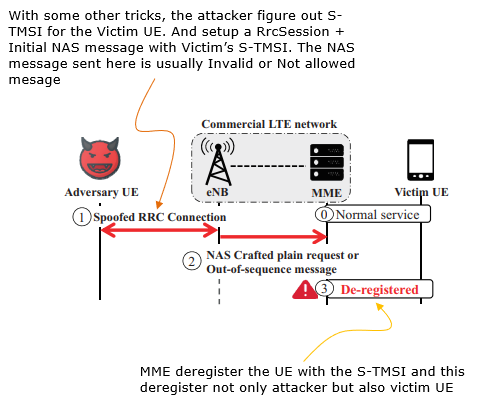

Remote de-registration attack

Source : Touching the Untouchables: Dynamic Security Analysis of the LTE Control Plane - Hongil Kim et al User Identification Attack by PHY layer hackingMost of the attacks described above was done by utilizing / analysing higher layer traffic (i.e, OTA signaling messages). However, the attack can be done at much fundamental level (i.e, PHY layer level). An example is illustrated below.

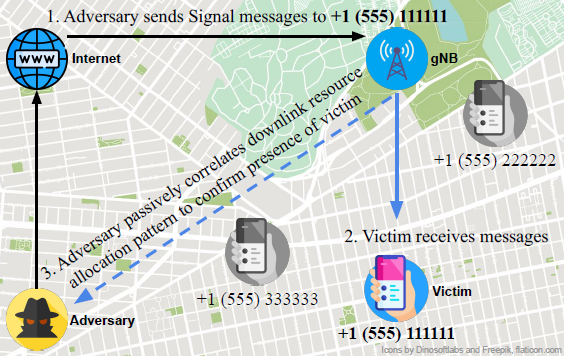

Source : From 5G Sniffing to Harvesting Leakages from Privacy-Preserving Messengers - Norbert Ludant et al This is the overall procedure of this type of attack

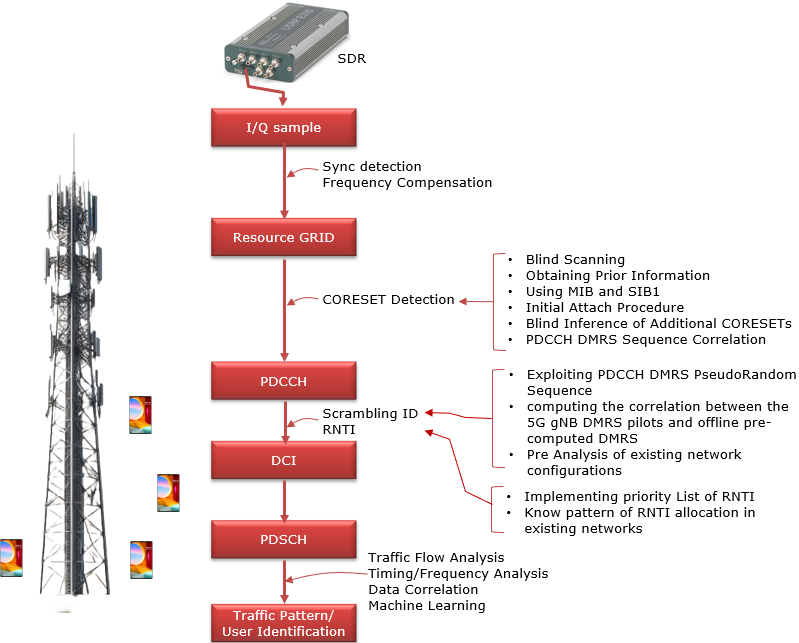

The key point for this type of attack is to decode PDCCH and eventually get direct access to user traffic. This is done as illustrated below. This is my own summary of the paper : From 5G Sniffing to Harvesting Leakages from Privacy-Preserving Messengers

Here goes the verbal description of the above diagram by the author of the paper - Norbert Ludant In order to obtain resource-scheduling information from a 5G cell, an attacker would need to decode the Physical Downlink Control Channel (PDCCH), which carries the Downlink Control Information (DCI), which ultimately contains information about resource scheduling. The DCI tells a user, addressed by its RNTI, which resources are directed to the user (DL traffic), or which UL resources to use to transmit its data (UL grant). The DCI contains information such as frequency and time domain resources allocated, the MCS used for the data, etc. By obtaining these DCIs, it is possible to infer the traffic of users in a given cell. In fact, some researchers have used this DCI information to determine which apps or type of service users are performing just by looking at the resources allocated to them, by using machine learning techniques. LTE sniffers were developed in the past, such as OWL or FALCON, but due to the increased complexity of the 5G RAN, developing a 5G Sniffer became more complicated. Some of the main difficulties come from changes in the encoding of the DCI, for instance, now the scrambling sequence uses as input both the RNTI and some scramblingID that is conveyed through protected RRC messages. This and other changes complicate considerably blindly decoding the DCI. In order to decode the PDCCH, the receiver obtains the IQ samples from the frequency band that the gNB is operating, and performs time and frequency synchronization, as a normal UE would do. Then, the receiver would need to know the Bandwidth Part and CORESET configuration. However, this is conveyed through RRC messages, such as RRC Reconfiguration/RRC Setup or in MIB/SIB. The best option is to obtain these values by connecting a COTS UE and obtaining these messages, as the connection remains static for long periods of time, and common to all users in a cell. Using this prior information, the CORESET and BWP can be configured. Alternatively, it would be possible to blindly scan for DCIs by using all possible combinations of values, until a DCI is found, and then use that configuration. Once the configuration is known, the PDCCH symbols have to be decoded to obtain the DCI bits. However, the attacker does not know the aggregation level (AL), the RNTI or scramblingID, or other required parameters. In this case, we optimize finding possible DCIs by finding the correlation with pre-computed PDCCH-DMRS symbols, which accompany each DCI, and are generated by a pseudo-random sequence with the scramblingID used as seed value. Other optimizations come from exploiting redundancy in the rate-matching block, allowing to early determine if an RNTI is valid, or by prioritizing previously seen RNTIs, etc. The decoded DCIs contain resource scheduling information that can be used for privacy-related attacks such as determining the presence of a user. In order to do so, an attacker would monitor a 5G cell, and decode all resource scheduling to all users. Then, it injects a specific traffic pattern that can be easily recognizable through the resource scheduling information. These patterns need to be robust against background traffic, delays in scheduling, and others. For instance, transmitting an ON-OFF signal which creates sharp peaks (e.g. transmitting 1 MB file periodically), leads to an easily recognizable pattern. The attacker then, will determine if the user is present in a specific cell, if its able to find the injected traffic pattern, and link the higher layer identity, such as phone number, to the RNTI, and determine that a user is present in a specific area delimited by the cell. In addition, the resource scheduling information can be used for other privacy-related attacks. For instance, researchers have shown that it is possible to analyze the traffic for a specific user and identify which apps/services are being used, or which Youtube video an user is watching. This can lead to fingerprinting of specific users based on their usage patterns Signal Overshadowing AttackIn cellular network attacks, Fake Base Stations (FBS), also known as rogue base stations, are a common method. These exploit user equipment (UE) by luring devices with stronger signals, establishing connections to extract sensitive information like IMSI, temporary identifiers, or communication data. This connection becomes the vector for attacks such as denial-of-service (DoS), tracking, or eavesdropping. The Signal Overshadowing Attack, however, introduces a new methodology. Unlike FBS, it requires no connection with the victim UE. Instead, it leverages the principle that receivers decode the strongest signal when multiple signals are transmitted at the same frequency. By transmitting a stronger signal, attackers can inject malicious messages directly into the victim UE. A key challenge is achieving precise timing and frequency synchronization with the legitimate base station. Attackers use synchronization signals like Primary Synchronization Signal (PSS) and Secondary Synchronization Signal (SSS) to align transmissions. This ensures that their stronger malicious signal overshadows the legitimate one. Once synchronization is achieved, the attacker passively collects information from unprotected broadcast signals like Master Information Block (MIB), System Information Blocks (SIBs), and Paging messages from legitimate base stations. These messages, inherently unprotected in LTE, provide critical parameters like network configuration and timing information. With synchronization and collected information, attackers can transmit malicious messages directly to the physical layer at a specific radio frame, exploiting precise timing and coordination. By leveraging these factors, they ensure that the malicious message arrives at the UE at the right moment to be processed instead of the legitimate message from the legitimate BTS. The technique relies on overpowering the legitimate signal, making it nearly impossible for the UE to distinguish between the two. By simply increasing the power of the malicious transmission, attackers effectively "overshadow" the original signal, forcing the UE to decode and process the malicious content instead. This deceptive manipulation of signal power and timing is the basis for the term "overshadowing." Overall concept of Signal Overshadowing Attacking can be illustrated as follows.

Image Source : Hiding in Plain Signal: Physical Signal Overshadowing Attack on LTE In the context of LTE signaling flows, understanding where, when, and how often to target specific messages is critical for executing effective signal overshadowing attacks. These attacks leverage vulnerabilities in the timing and structure of LTE communications, particularly during key stages of connection establishment and message exchange. Broadcast messages, such as the Master Information Block (MIB) and System Information Block (SIB), are ideal targets because they are transmitted periodically and lack encryption or integrity protection. Similarly, unicast messages, like RRC Connection Release or Paging messages, present opportunities for manipulation, especially before the security context is fully activated. Attacks must be precisely timed to align with the broadcast intervals or specific signaling events, ensuring that malicious signals overshadow legitimate ones without disrupting overall decoding. The frequency of these attacks depends on the type of message being targeted, with broadcast message injections synchronized to periodic transmissions and unicast message injections strategically timed to exploit security gaps in real time.

Signal overshadowing attacks in LTE networks open up a range of malicious use cases that exploit vulnerabilities in the system's broadcast and signaling protocols. From overwhelming the core network with a Signaling Storm, selectively disabling services through Selective DoS, bypassing security mechanisms with IMSI Paging, to manipulating public behavior via Fake Emergency Alerts, these attacks highlight the risks posed by unprotected and insecure channels. Each of these use cases demonstrates how an attacker can target specific elements of the LTE signaling flow to disrupt operations, compromise security, and exploit user trust, often with minimal resources and low chances of detection.

The SigOver attack offers several advantages over the Fake Base Station (FBS) method in LTE signal attacks:

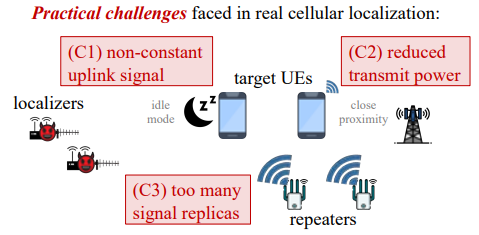

Uncooperative Multiangulation Attack (UMA)The Uncooperative Multiangulation Attack (UMA) is a method used to locate mobile devices that do not cooperate or actively share their location. It works by taking advantage of weaknesses in LTE networks. UMA forces the device to continuously send signals and increases the strength of these signals to make them easier to detect. Using these signals, it calculates the device’s exact location, even in difficult situations, such as when the device is transmitting in low power or signal interference occurs in normal condition. It does not require access to private parts of the network or permission from the device being tracked. Finding the location of mobile devices are is really important for things like helping police, ambulances, and people who manage phone networks. But finding devices that don't want to be found is super tricky. Usually these devices try to hide their location or don't send out signals frequently. UMA is a technique to resolve these issues and enables the positioning of specific UEs. The answer to this question is well illustrated in following diagram.

Image Source : Enabling Physical Localization of Uncooperative Cellular Devices This illustration presents the challenges faced when localizing devices in realistic scenarios, which are far more complex due to real-world factors:

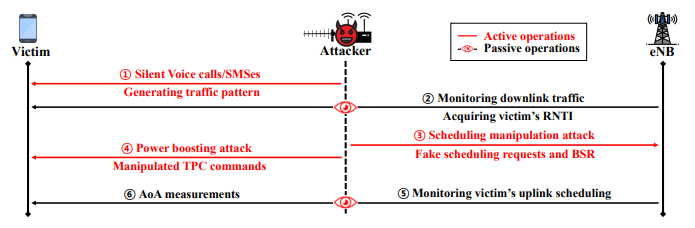

The answer to this question is well illustrated by the following sequence diagram. It highlights the sequence of steps an attacker follows to physically locate a target device (victim) by exploiting LTE network vulnerabilities. The process includes both active operations (red arrows) and passive operations (eye symbols), detailing how the attacker interacts with the victim, the eNodeB (eNB, base station), and the network.

Image Source : Enabling Physical Localization of Uncooperative Cellular Devices Followings are breakdown description of the sequence

There are so many types of attack that can be done by this technique as listed below. Some of the attack model are described in Enabling Physical Localization of Uncooperative Cellular Devices and others are from chatGPT.

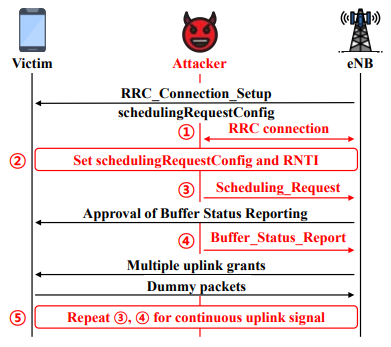

Image Source : Enabling Physical Localization of Uncooperative Cellular Devices Following is break down description of the sequence diagram USIM AttackThe USIM (Universal Subscriber Identity Module) plays a critical role in mobile communication, serving as a secure element that stores user credentials and enables authentication with cellular networks. However, as the bridge between the user and the network, the USIM is also a potential target for various security threats. USIM attacks can range from attempts to intercept sensitive data to manipulating authentication protocols, exposing users to risks like unauthorized access, data theft, and identity spoofing. Understanding the vulnerabilities and implementing safeguards around USIM security is essential for maintaining the integrity of mobile communications. Several typical ways an attacker could gain control of a SIM card are

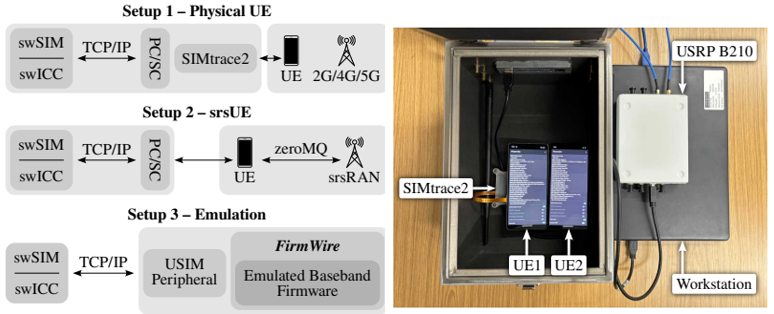

Recently I found a well documented paper on this subject which is SIMurai: Slicing Through the Complexity of SIM Card Security Research. Followings are brief highlights from the paper. Key arguments and findings : SIM cards' privileged access to a device's baseband, combined with often outdated security measures, makes them vulnerable to exploitation, which tools like SIMURAI can analyze by emulating SIM behavior for research purposes

Followings are brief descriptions of each setup :

Controlling a SIM card to launch attacks can be achieved through various methods as listed below.

Once a SIM is controlled through one of these methods, it can launch various attacks against the mobile device and its baseband. Some examples demonstrated or discussed include:

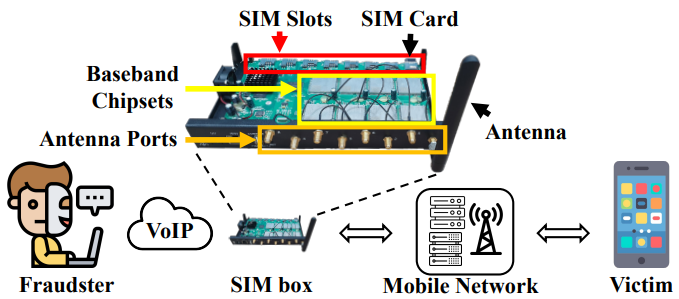

SIMBoxA SIMbox is a piece of hardware that can hold anywhere from a handful to several hundred mobile-network SIM cards. It sits between the internet (often a VoIP soft-switch) and the radio access network. When an international call or A2P SMS reaches the VoIP side, the SIMbox selects one of its local SIMs, dials the called number over the air interface, and makes the traffic look like an ordinary on-net or domestic call. From the serving network’s point of view, the device behaves like a swarm of normal handsets that just happen to live in the same rack. This lets the fraudster pocket the difference between high-margin international termination rates and the low local retail tariff—or avoid paying altogether.

Image Source : Preventing SIM Box Fraud Using Device Model Fingerprinting A SIM box may start out looking like an ordinary fraud toolkit for shaving off international-termination fees or pushing phishing calls, but the moment those hundreds of prepaid cards sit in one rack it becomes a genuine security problem for a mobile network. First, it destroys identity integrity. Because each SIM was activated with forged or throw-away credentials, every voice call and SMS that the core network logs appears to come from a legitimate domestic subscriber even though the real caller is overseas and completely untraceable. That breaks lawful-interception workflows: investigators who follow the IMSI or calling-line ID end up at a dead end. The same device manipulates the caller-ID field so the target’s phone displays a familiar local number. That makes voice-phishing and smishing far more convincing, and when a victim sends back a one-time password the SIM box can receive it instantly through one of the other SIMs in its pool. Meanwhile, the radio side suffers. Hundreds of “virtual handsets” camp in a single cell, attaching and detaching in rapid rotation to avoid usage caps. The paging storms and signalling spikes this generates degrade quality of service for nearby customers and can mask other anomalous traffic. Because all of that activity is concentrated in one physical spot, a motivated attacker can treat the farm as a low-cost measurement probe. By logging broadcast channels and system information blocks across many SIMs, they can map operator frequencies, power levels and mobility parameters with far greater detail than a normal handset could provide. Those measurements feed directly into the design of targeted jammers, IMSI catchers or RRC-layer exploits. In other words, a revenue-skimming appliance quietly widens the attack surface of the entire RAN. Finally, the accounting distortion matters. All of the grey-route traffic is recorded as domestic, so the operator’s traffic forecasts, capacity planning and even security-appliance sizing rely on polluted data. Investment is steered toward the wrong cells, and firewalls or DPI platforms are scaled for an inaccurate threat picture. What begins as a commercial loss therefore evolves into a systemic weakness: reduced visibility, slower incident response and an environment in which more serious attacks can hide in plain sight.

The techniques summarized below illustrate the layered approach operators use to detect and shut down SIM-box fraud. Each method focuses on a different observable “signature,” from deliberately seeded probe calls and historical CDR patterns to radio-frequency fingerprints, SIM-to-device binding anomalies, machine-learning–driven anomaly scoring, and cross-border location inconsistencies. While no single technique is fool-proof—probe routes can be whitelisted, analytics lag behind real-time abuse, and RF clustering may misclassify dense offices—their combined use allows a fraud-management system to surface suspicious traffic quickly, prioritize investigations, and bar offending SIMs before they can rotate out.

For a cellular-security engineer, the lesson is that SIM-box fraud does not exploit weaknesses in air-interface ciphers but in the business-logic and identity layers of the network, producing a dual threat: direct economic loss through bypassed termination fees and degraded quality of service, and operational risk as spoofed identities frustrate lawful interception and enable large-scale social-engineering campaigns. Because fraudsters can swap SIMs in seconds, the effectiveness of a defence hinges on how fast anomalies are detected—real-time, machine-learning analytics fed by signalling, billing and location data dramatically outperform slow batch reports. Ultimately, success depends on orchestrating controls across radio access, core signalling, billing policy and regulatory enforcement; no single layer, acting alone, can shut down a well-run SIM-box operation.

FuzzingFuzzing is an automated technique that bombards an implementation with massive numbers of deliberately malformed or semi-valid inputs and watches for crashes, hangs, memory-safety errors, or protocol violations. In the cellular world those inputs are air-interface frames, control-plane messages, core-network APIs, or even whole baseband-firmware packets, rather than ordinary files or HTTP requests.

Fuzzing in cellular networks is both a double-edged sword and a necessity. Offensively, it lowers the barrier to high-impact baseband and core-network attacks; defensively, it is currently the most effective way to stress-test the sprawling, fast-evolving 4G/5G stack. The engineering frontier lies in state-aware, performance-efficient, spec-driven fuzzers that can keep pace with Rel-19/6G complexity without requiring a full RF lab for every campaign. Attackers run fuzzers for exactly the same reason defenders do—but they keep the crashes for themselves. A rogue base-station or malicious SIM application can continuously spray tampered RRC, NAS or PFCP messages, hoping to:

In the attacker’s playbook, OTA fuzzing is the practice of broadcasting mutated radio-layer messages to nearby devices with the explicit goal of crashing baseband firmware or coercing it into executing injected code. Instead of validating a product in a lab, the adversary uses the same automation loop—generate, transmit, observe, refine—to turn protocol edge-cases into reliable exploits that travel invisibly over the air. For threat actors, OTA fuzzing turns the air interface into an invisible attack surface that bypasses app-store vetting, phishing filters, and even OS-level hardening. A single unpatched baseband bug can yield silent RCE against every phone in range—illustrating why defensive teams now treat radio-layer fuzz results with the same urgency as critical CVEs in web browsers or VPN gateways. Generate a hostile corpus “Generate a hostile corpus” refers to the preparatory phase of an over-the-air (OTA) attack in which an adversary systematically produces thousands—or even millions—of carefully mutated cellular-protocol messages intended to stress or break a target device’s baseband stack. Rather than tossing random noise onto the airwaves, the attacker uses protocol-aware tools, coverage-guided fuzzers, and even AI-driven generators to craft inputs that are malformed just enough to probe deep parsing logic while still passing basic sanity checks. The resulting message set—the hostile corpus—becomes the ammunition that is later transmitted via a rogue cell or malicious user equipment to crash, confuse, or hijack nearby phones.

Weaponize the payload over RF Once a crash-inducing frame is distilled, the attacker integrates it into a rogue cell or malicious UE built on open-source stacks (e.g. srsRAN, OpenAirInterface) and transmits via a software-defined radio (SDR). Because cellular devices automatically select the strongest or most attractive cell, nearby phones may camp on the attacker’s signal without any user interaction. Mutated control messages—now riding on legitimate timing, scrambling, and power—reach the modem exactly as if they came from a commercial network. Trigger, persist, and pivot

This is about the post-delivery phase of an OTA baseband attack, where the attacker turns an initial crash or foothold into sustained control and broader impact. Once the malicious radio payload reaches the modem, the adversary may first induce repeated crashes and reboots that sap battery life or deny service, but a more sophisticated exploit leverages memory-corruption bugs to achieve remote code execution that hides entirely inside the baseband firmware. From that invisible stronghold, the attacker can pivot through high-speed inter-processor links into the application processor, escalating their privileges to exfiltrate data, scrape voicemail, or fully compromise the device Why OTA fuzzing is attractive to adversaries Over-the-air fuzzing offers attackers a uniquely potent blend of stealth, scale, and convenience. Because mutated signalling traffic looks indistinguishable from everyday radio chatter, adversaries can deliver exploits without links, prompts, or any user interaction. The global reliance on just a handful of baseband chipsets means that a single flaw discovered in one model can instantly imperil millions of devices. Crucially, many vulnerable parsers operate before cryptographic handshakes occur, giving attackers pre-authentication reach into even the most up-to-date 5G handsets. And since most fuzzing and exploit development can be performed quietly in emulators, the only on-air activity involves short, low-power transmissions—minimizing legal exposure while maximizing impact.

Real-world echoes Various public disclosures show that OTA fuzzing is not hypothetical; coordinated vulnerability efforts have forced firmware updates across major Android vendors and pushed 3GPP to tighten message-length checks. The same research also demonstrates how quickly a crash found in emulation can be ported to an SDR and reproduced in the field. Barriers attackers still face Even the most sophisticated over-the-air attackers must contend with practical and technical hurdles that limit the scale and reliability of their campaigns. To begin with, a rogue cell has to overpower legitimate towers in the same area, so wide-area exploitation typically demands a physical presence in high-foot-traffic locations such as airports or stadiums. On the device side, new chipsets increasingly employ hardening features—memory-tagging, pointer authentication, and fine-grained control-flow integrity—that raise the bar for turning a crash into stable code execution, even though older LTE code paths may still lag behind. Finally, regulators and operators are sharpening their response: continuous spectrum monitoring and RF-fingerprinting can expose unauthorized SDR activity, pressuring attackers to rely on brief “hit-and-run” transmissions before they can be traced.

When defenders embrace fuzzing, it becomes a proactive quality-assurance step rather than an attack tool, threading directly into the CI/CD pipelines that build and deploy radio-access and core-network software. By continuously generating protocol-aware mutations, measuring code-coverage feedback, and running thousands of test cases per second on emulated baseband firmware, engineers can discover deep-seated parsing faults and logic errors long before a product ever hits the field. The approach is not theoretical: campaigns such as RANsacked have already uncovered well over a hundred implementation flaws and forced dozens of CVE assignments across both commercial and open-source cellular stacks, underscoring fuzzing’s value as a frontline defensive technique.

The payoff is real: the RANsacked campaign uncovered 119 implementation flaws and triggered 93 assigned CVEs across seven commercial and open-source cores. Fuzzing cellular systems is far more intricate than throwing random packets at a stateless protocol: every mutated message must navigate strict call-flow sequencing and tight timing windows, survive deeply nested ASN.1 grammars, and often pass through layers of encryption and integrity protection before it can reach the vulnerable code paths that matter. This complexity is compounded by practical hurdles—booting entire core networks or SDR stacks for each test dramatically reduces throughput, radio transmissions are restricted by spectrum regulations, and the message specifications themselves evolve with every new 3GPP release. As a result, successful fuzz campaigns demand state-aware harnesses, auto-generated parsers, clever snapshotting or re-hosting techniques, and relentless upkeep to stay in lockstep with an ever-shifting standard.

Reference

YouTube

PodCast

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||